“This job is killing me” is not a statement of jest. It is a desperate plea of outright sincerity.

“This job is killing me” is not a statement of jest. It is a desperate plea of outright sincerity.

Stress, anxiety, depression – all have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality. But can interventions to help people cope with stress positively affect longevity and decrease risk of dying? The results of a new study in the Archives of Internal Medicine would imply the answer is an encouraging “yes.”

Constructively dealing with stress is easier said than done, but it would seem logical that if we can reduce our psychological and social stressors we might live longer and delay the inevitable wear and tear on our vessels. This study proved that one such intervention, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients who suffered a first heart attack, lowered the risk of fatal and nonfatal recurrent cardiovascular disease events by 41% over eight years. Nonfatal heart attacks were almost cut in half. Excitement may be dampened by the fact that all-cause mortality did not statistically differ between the intervention and control groups, but did trend towards an improvement in the eight years of follow up.

Definitely less suffering. Maybe less deaths.

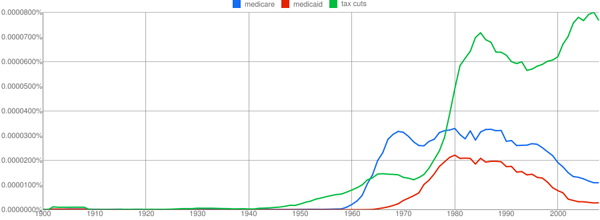

The authors state that psychosocial stressors have been shown to account for an astounding 30% of the attributable risk of having a heart attack. Chronic stressors include low socioeconomic status, low social support, marital problems, and work distress. Emotional factors also correlated with cardiovascular disease include major depression, hostility, anger, and anxiety.

An experienced and specifically trained psychologist usually directs cognitive behavioral therapy for patients. It has been proven to help conditions ranging from social anxiety to borderline personality disorder. While such therapy is by definition supervised and directed by a professional, perhaps we can benefit from a crude understanding of its methods.

In this study, the CBT focused on 5 key components – education, self-monitoring, skills training, cognitive restructuring, and spiritual development. It emphasized stress management, coping with stress, and reducing the experience of daily stress, time urgency, and hostility. The program was highly structured, performed over 20 two-hour sessions during the course of a year.

Education – the goal was for participants to learn more about cardiovascular disease, specifically about anatomy, physiology, symptoms, consequences, the relationship between stress and heart disease, and the symptoms and signs of stress.

Self-monitoring – this goal encompassed becoming more alert to body signals of stress such as heart rate, muscular tension, and pain, with greater attention to behavioral and cognitive clues. This was accomplished in part by the use of diaries to observe, monitor, and reflect upon reactions and behaviors, as well as the use of group processes to enhance observational skills and understanding.

Skills training – this goal was to reduce negative thinking, and to learn to act constructively rather than simply reacting to everyday problems. I’ve heard this method described elsewhere as the imperative to “respond, not react.” A drill book was used for daily behavioral exercises, practicing alternatives to anger, frustration, and depressive reactions. Problem solving and communication skills were rehearsed in the group setting as well.

Cognitive restructuring – this goal involved recognizing negative, hostile, and stress-triggered thoughts and attitudes. Efforts were made to change the participants “internal dialogue” through constructive self-talk, focusing on hostility, worries, and self-defeating attitudes. This component seems to have relied the most on the specialized training of the psychologists to deliver a restructuring of maladaptive thinking styles, again through individual and group efforts

Spiritual development – the goal was to encourage a spiritual reflection upon life, and what is desired for the future. Individual goals, quality of life, and the importance of significant others were discussed. The social and emotional support of the group helped foster self-esteem, optimism, trust and emotional intimacy.

The structure of each session was similar to most CBT programs. This included a weekly specific theme, starting each session with progressive muscular relaxation, followed by reflection and discussion of homework assignments. The current theme was discussed and tied in with previous and new themes, ending with a new homework assignment, often individually tailored. A variety of educational media and materials were used.

Specific skills and themes were tailored to the participants, and the authors noted a predictable (if not clichéd) pattern. Women more often needed focus on self-confidence and self-assertion skills, while men were more often in need of ways to cope with aggressive and hostile behavior.

Another gender difference centered around social networks. Women were often over-involved with social ties, subduing their own self-interests, while men’s social networks tended to provide more unconditional support. (I would also insert another cliché here that men I see in my own practice often suffer from poor tending to social ties, and consequent isolation).

Limitations of this study include the population of patients studied – over 90% were white and of Swedish ancestry, and over 75% were male. There was an overall all-cause decrease in mortality for those attending the CBT program, but this tendency did not meet statistical significance. Prior similar studies have shown conflicting results of stress reduction programs, some concluding that stress management does not affect cardiovascular mortality. However, the authors also reference 2 meta-analyses of health education and stress management programs for patients with coronary artery disease that found a pooled 34% reduction in cardiac mortality and a 29% reduction in recurrent heart attacks. Meta-analyses are generally considered to be of higher authority than individual trials since the evidence they collect is from multiple independent trials.

So what does this study mean?

Perhaps in a broad sense we can confirm our intuitive sense that stress is harmful to us. A stressful job, aggressive people, a bad relationship, depression, and anxiety all place undue wear and tear not only upon the health of our psyche, but also upon the health of our very substance. More importantly, our hearts and minds can benefit from everyday measures to reduce stress, and to deal constructively and optimistically with the internal and external battles we face.

Participation in a supervised cognitive behavioral therapy group, especially after one suffers a first heart attack, seems like a good idea, and might just prevent or delay a significant burden of recurrent cardiovascular disease.

At the very least, studies like this reaffirm our collective need to step back, to reflect upon the pace and tenor of our strident lives, and to methodically work on a less reactive response to our daily conflicts. It is almost as if an empathic approach to ourselves is needed, one that genuinely considers our woes with some healthy distance, perspective, and practiced coping skills.

Respond, don’t react.

Study Citation:

Randomized Controlled Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs. Standard Treatment to Prevent Recurrent Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease: Secondary Prevention in Uppsala Primary Health Care Project (SUPRIM)

Arch Intern Med. 2011; 171(2): 134-140.