I’ve decided to join the conversation on Twitter, so if you’re into that, here I am:

http://twitter.com/examiningroom

Dr. Charles was already taken. Doh!

My grandfather was a country doctor, and somewhat of a local legend. Grown men would introduce themselves to him at July 4th parades, shaking the knobbed hands that once delivered them safely into the world. Women would drop off baskets from their gardens, full of bright green peppers and juicy red tomatoes, living products of the earth which in a way symbolized the regeneration he aimed to effect. But at the end of his life I would watch him sitting alone, retired to an old chair, in the shade of the crumbling barn behind his house. His clothes were chosen for comfort, his beer for ease of swallowing, and his facial expression for the complicated memories haunting his thoughts. He would watch the clouds for hours.

Now a family doctor myself, I wonder what he saw in those clouds. Each one is a vague message, some inscrutably beautiful, most others frighteningly unstoppable as they drift across skies of blue, grey, and violet at the end of day. I can see daydreams of cured patients taking shape in puffy white whorls, before morphing into stillborn infants cradled by weeping mothers. There is an absurd distance between the earth and the sky above. Another cloud passes, unloads its burden, accepts a sprinkling of advice, and then floats on to be shredded or lifted by future winds.

A doctor’s career is surely marked by triumphs, but the very nature of life ensures many defeats. I hold hands robbed of strength by strokes, look into eyes hollowed by Parkinson’s, read MRI reports of nightmarish creatures nestled in brains, and I cannot rewrite the stories. Tears are shed over jobs lost, parents suffering and dying, sons killed in car accidents, daughters possessed by addictions, even family pets mercifully put to sleep. I consider the very act of getting out of bed each day an act of heroism for the self aware.

Attending to human misery is a daily task of doctors, social workers, nurses, counselors, pastors, and all the listeners. At times it is overwhelming. Compassion fatigue is a natural result, and a doctor’s sudden lack of empathy might be that day’s defense mechanism instead of an enduring character flaw. To be a doctor, to be blamed when things go badly, to endure the barbarism of a lawsuit that seeks to personify you as the source of outrageous fortune… it’s certainly enough to make you cast your eyes up to a weightless sky.

I know my grandfather achieved much, helped many, but it was a melancholy greatness known by any physician who takes an honest measure of his calling. There are just too many broken bones, broken hearts, and broken lives.

So what do we accomplish, and what do we gain from our life’s work? At the end of each day we should only be enriched by the human bravery we’ve witnessed in defiance of adversity and disease. We can only be humbled by those who fight chaos with story, inspired by those who challenge nihilism with purpose, moved by those who negate despair with hope. We can only listen, counsel, and when invited into another’s private hell, walk gently and resolutely. We can only accept that one day it must be our turn, and that every day we must seek to create happiness. We must exalt the woman who walks in front of us, proudly, with her body full of cancer, as we search the clouds, hoping for a kind summer rain.

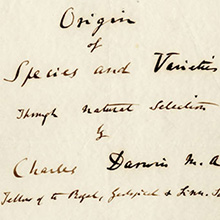

Last month I visited an exhibit entitled Dialogues with Darwin held at the American Philosophical Society Museum. On display are original handwritten letters by Darwin to other eminent scientists, manuscripts such as his handwritten title page for On the Origin of Species, rare first editions of his work, and handsomely illustrated books by other scientists.

Last month I visited an exhibit entitled Dialogues with Darwin held at the American Philosophical Society Museum. On display are original handwritten letters by Darwin to other eminent scientists, manuscripts such as his handwritten title page for On the Origin of Species, rare first editions of his work, and handsomely illustrated books by other scientists.

The exhibition traces the history of his theory of evolution, and contrasts it with competing ideas of the time, some of which now seem quite bizarre. For those not wanting to trek all the way to Philly (I was at a conference already), there is an amazingly good online museum tour in which you can get the same virtual experience as seeing the originals.

A few reflections from my visit:

As a physician I consider Darwin’s contributions to science particularly relevant. His theory of evolution sparked new advances in the fields of genetics, embryology, and epidemiology. Natural selection as a process drives the age-old battle between mankind and disease. It keeps us forever entangled in a race against drug-resistant microorganisms and new viral scourges. Learning about the evolutionary origins of certain diseases may provide hints about how to better treat them. Understanding the basic processes of evolution has helped us better comprehend many genetic diseases that are inherited from one generation to the next.

As a physician I consider Darwin’s contributions to science particularly relevant. His theory of evolution sparked new advances in the fields of genetics, embryology, and epidemiology. Natural selection as a process drives the age-old battle between mankind and disease. It keeps us forever entangled in a race against drug-resistant microorganisms and new viral scourges. Learning about the evolutionary origins of certain diseases may provide hints about how to better treat them. Understanding the basic processes of evolution has helped us better comprehend many genetic diseases that are inherited from one generation to the next.

Critics of evolution often point to sinister eugenics thinking (exemplified by Nazi Germany) as evidence of the theory’s evils. But Darwin consistently fought against the notion that his theory justified racial inequalities as the natural ends of selection. For example, he strongly disagreed with Josia Nott, who in 1854 published this racially prejudiced catalogue of different human species:

Not only are these drawings obvious caricatures, but the suture lines in the skulls were drawn with false variations between “species” of men. Real skulls in different peoples of the world are quite similar, and the list of misconceptions only starts there…

The question that generates the most controversy to this day is what does evolution imply about religion, and specifically about a “Creator?” The Museum notes that Darwin does not address the origin of life in his first edition of On the Origin of Species. Perhaps his reluctance to set off a firestorm of religious condemnation (and other reasons) played a part in delaying the publication of his ideas (first conceived in 1837) until 1859. In the 2nd British edition he inserted “Creator” into the book’s last paragraph. Letters show he later regretted it as a response to public pressure, and that he meant the term to refer to “the unknown.” Darwin was a self-proclaimed agnostic publicly.

I had the privilege of visiting Charles Darwin’s grave one week to the day after his 200th birthday. I was traveling in London and visited Westminster Abbey, where despite his apparent wishes to the contrary, he was buried in the hallowed religious landmark among England’s greatest figures. It is apparent to this day that religious leaders are conflicted about him, as his tombstone is rather unceremoniously marked. If you weren’t specifically looking it would be easy to miss. It is comically juxtaposed with the extravagant tomb of the more pious Isaac Newton. Even the Westminster Abbey official tourist pamphlet observing Darwin’s 200th birthday spent most of its words lamenting his “unfortunate” loss of religion instead of discussing his contributions to science.

I came away from the exhibit with a great respect for Darwin as a synthesizer of ideas. Among the disparate influences in his life that led to his unifying theory, one can count his grandfather’s poetry, his early training in geology and his correspondence with geologist Charles Lyell, his legendary voyages aboard the H.M.S. Beagle collecting and comparing biological specimens, his reading of Thomas Malthus and economic theory, and even his study of theology. Theologist William Paley argued that the sheer complexity of nature required a “Maker,” with which Darwin agreed, but replaced a maker with a process – natural selection. Many clergy of the time reconciled this truth with their religion by considering “natural selection” a tool wielded by God, while others greatly condemned Darwin.

Early in his career Darwin considered himself a geologist. The small forces like wind and rain, which over millions of years erode mountains, convinced him that small variations in living things over millions of years could also be a powerful force, adding up to a dizzying array of life.

Thomas Huxley’s iconic drawing of 1863 (four year after On the Origin of Species was published) served as a more compelling visual argument of man’s place in nature being not that different from other animals. The drawing incorrectly implies a direct lineage or progressive march, but did open the doors to a question that Darwin had avoided (and spawned a lot of creative t-shirt designs). He published The Descent of Man in 1871.

It is interesting that the word “evolution” is never used in On the Origin of Species. The word “evolved” is only used once. It is the last word of the book:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been and are being, evolved.

The museum, in keeping with its dialogues theme, reserved two bulletin boards for sticky notes upon which visitors could write their reactions to the exhibit. There were the predictable quarrels between those naming the Bible as the only source of knowledge they needed, and those who feel religion is the source of all evil. But there were also more nuanced arguments and opinions, and the museum also has an online forum to continue this dialogue. If you check out the online exhibit, you may want to contribute your thoughts. They also ask whether Darwin would have been a blogger were the medium to exist in his day. I tend to think he would have blogged his voyages as a young man upon The Beagle, but that his more reserved tendencies would have kept him from the acid debate that rages today.

Darwin is remembered for his eloquence as well as his ideas. His correspondence is gentle, respectful, and intellectually curious, even if his handwriting is atrocious. He suffered from an array of medical ailments and symptoms during his lifetime, and at one point had consulted over 20 baffled doctors. In retrospect his ills have been attributed to diseases as diverse as Chagas Disease to Anxiety… I’ll pick up with the medical aspects in the next post.

Darwin is remembered for his eloquence as well as his ideas. His correspondence is gentle, respectful, and intellectually curious, even if his handwriting is atrocious. He suffered from an array of medical ailments and symptoms during his lifetime, and at one point had consulted over 20 baffled doctors. In retrospect his ills have been attributed to diseases as diverse as Chagas Disease to Anxiety… I’ll pick up with the medical aspects in the next post.

The CDC just reported a study of 77 people who died of the H1N1 swine flu, finding that 22 of those unfortunate 77 had evidence of bacterial coinfection in the lungs – meaning that bacterial pneumonia as well as the direct effects of viral H1N1 may have contributed to death.

In prior flu pandemics it is known that bacterial pneumonia was often responsible for many deaths. The initial viral infection seems to set the stage for a one-two punch.

In this newest study, bacterial coinfections caused by S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and group A Streptococcus were proven using modern techniques on postmortem lung tissue samples. Out of the 22 samples found to have bacterial infections, the most common pathogen isolated was Streptococcus pneumoniae.

These results cannot be used to determine the prevalence of bacterial coinfection in all fatal cases due to several limitations (including the fact that not all possible bacteria could be tested for, knowledge of the final cause of death in some patients was limited, and tissue samples may have been collected from unaffected portions of the lung).

The actual study details can be found here at the CDC’s MMWR site, or read in a watered down summary on Web MD, or Wall Street Journal Coupon. The investigators’ conclusion:

The findings in this report also underscore the importance of managing patients with influenza who also might have bacterial pneumonia with both empiric antibacterial therapy and antiviral medications. In addition, public health departments should encourage the use of pneumococcal vaccine, seasonal influenza vaccine, and, when the vaccine becomes available, pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine.

While I am certainly not perfect, nor in the vanguard, nor necessarily right, I have treated “patients with influenza who also might have bacterial pneumonia” with both Tamiflu and an antibiotic. I can imagine some colleagues at first glance cringing at what seems like unnecessary or indecisive over-prescribing. But treatment decisions are often made based upon the convergence of past experience, luck, and clinical judgement. It is reassuring when the evidence gives credence to what feels intuitive, and confirms that past is prelude in terms of our human history with viral influenza pandemics and bacterial pneumonia.

It may be helpful for patients and clinicians to be aware of this latest report from the CDC, and to redouble efforts to vaccinate those for whom pneumococcal and flu vaccines are indicated. The challenge to decide “is it viral or is it bacterial” exemplifies a way of thinking that tries to balance appropriate antibiotic use with over-prescribing that creates resistance and side effects. But the viral-bacterial dichotomy may not be mutually exclusive if we are to carefully consider this CDC report, and may better inform what treatment decisions should be made for those who are ill.

The cigarette smoke in bars used to be overwhelming for me. Before smoking was banned (locally), a trip to a watering hole for a drink with friends used to be quite disgusting. My eyes would burn. My throat would hurt. My voice would sound hoarse and leathery by the end of the night, and even the food and drink tasted as if it were lightly seasoned with tar. My clothes would stink so much that I upon returning home I would have to hang them up on the outside furniture to air out overnight. In my college days, weekends spent at bars were often followed by weekdays of sinusitis. I resented the crowds with their destructive exhalation of smoke into my lungs so much that I stopped going completely (not really, but that sounds righteous). And for a man who enjoys a good beer with conversation, this was tragic.

The cigarette smoke in bars used to be overwhelming for me. Before smoking was banned (locally), a trip to a watering hole for a drink with friends used to be quite disgusting. My eyes would burn. My throat would hurt. My voice would sound hoarse and leathery by the end of the night, and even the food and drink tasted as if it were lightly seasoned with tar. My clothes would stink so much that I upon returning home I would have to hang them up on the outside furniture to air out overnight. In my college days, weekends spent at bars were often followed by weekdays of sinusitis. I resented the crowds with their destructive exhalation of smoke into my lungs so much that I stopped going completely (not really, but that sounds righteous). And for a man who enjoys a good beer with conversation, this was tragic.

When the local smoking ban was proposed there were predictable outcries from business owners who feared that a restriction of their patrons’ rights to inhale burning cigarettes would lead to financial ruin. Some complained about a government intrusion on personal freedom, even as these same folks ignored their own intrusions upon the freedom of the air we are obligated to share. Still others privately worried about gaining weight from smoking cessation. But finally a ban passed, and then another, and another, and I was able to enjoy the bar atmosphere as well as the cold, preferably craft beer in my hand once again. No more respiratory problems, stinking clothes, or carcinogenic ambience.

Recently some amazing health evidence has surfaced since the advent of smoking bans:

Bans on smoking in public places have had a bigger impact on preventing heart attacks than ever expected, data shows. Smoking bans cut the number of heart attacks in Europe and North America by up to a third, two studies report… the results of numerous different studies collectively involving millions of people, indicated that smoking bans have reduced heart attack rates by as much as 26% per year.

Second-hand smoke is thought to increase the chances of a heart attack by making the blood more prone to clotting, reducing levels of beneficial “good” cholesterol, and raising the risk of dangerous heart rhythms.

It makes you wonder what savings we could achieve in the health care budget if people no longer smoked first hand, and what personal tolls of misery could be prevented in terms of suffering from cancers, obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease. A 26% decrease in heart attacks. That is astounding. How much money would we need to spend on pills taken daily by the entire country to effect that same reduction? Surely it would be in the billions.

So what if we no longer had to breathe in the combustion products of oil? What if guns were banned? Motorcycle helmets made mandatory? High fructose corn syrup and highly processed fast food strictly limited in our diet? Tanning beds discouraged? Kanye West silenced? The list could go on, with varying ideologies becoming increasingly piqued (go ahead and add your gripe)… but putting our freedom of questionably bad choices aside, and simply considering health and wellness, so much could be done to improve the petri dish in which we must all coexist.

But if you live in an area with a smoking ban, at least you can taste a good beer again, with less ambient harm and smelliness, and just maybe you won’t have that heart attack you might have had during some awful day in the future.

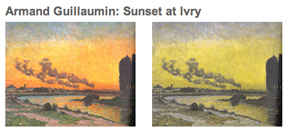

If you were color bind, and a new genetic therapy were developed that allowed you to see the full spectrum of visible light accurately for the first time in your life, would you pursue the treatment? Or would you accept the washed out, sepia world you were accustomed to, embracing the notion that you’re not quite seeing the full red-green majesty everyone else is? With the recent announcement of ongoing successful research into gene therapy that corrects the inherited deficiencies of color blindness (in monkeys), such a choice between the muted colors of the status quo and the brilliant rainbow of tomorrow may soon become a reality for the 1 in 12 people (mostly men) on the planet with color blindness.

If you were color bind, and a new genetic therapy were developed that allowed you to see the full spectrum of visible light accurately for the first time in your life, would you pursue the treatment? Or would you accept the washed out, sepia world you were accustomed to, embracing the notion that you’re not quite seeing the full red-green majesty everyone else is? With the recent announcement of ongoing successful research into gene therapy that corrects the inherited deficiencies of color blindness (in monkeys), such a choice between the muted colors of the status quo and the brilliant rainbow of tomorrow may soon become a reality for the 1 in 12 people (mostly men) on the planet with color blindness.

At first it would seem like an easy decision. To see the true magnificence of the reds of the Grand Canyon, the proper brilliance of a bouquet of fresh cut flowers, the beauty of a Cezanne, the subtle colors of the dazzling stars in the Milk Way – if suddenly these were alive instead of drab, it might feel like an even greater miracle, as if blindness itself had been lifted. There would be standard concerns that anyone would have with a new treatment, such as safety, long-term efficacy, and adverse effects. But amid all the media reports of new “hope for millions of sufferers,” I wonder if changing the color of the visible world might have additional, almost existential concerns to consider. Perhaps someone accustomed to a certain palette of color would be upset with the sudden change? What if the new palette looked riotous, awash in harlequin colors, like a television set to a ridiculous level of contrast?

Might seeing the world in a new light create anxiety? Imagine suddenly taking off a pair of rose-colored sunglasses that you had worn for the past 50 years and seeing the new-fangled shades of the trees, sidewalks, and people around you. Your wife’s “olive complexion” now makes sense in a green sort of way, and her auburn hair makes her look suddenly ridiculous to your brain’s sensibilities. The once-calming-if-bland sunsets over a blue bay are now a frightening bonfire of reds, churning in the sky like a kaleidoscope.

In curing a person’s deficiency of color perception, is there also a sense that an imperfection integral to identity has been lost? Does the cute girl with the big nose look at the new Anglo-button in the middle of her face after surgery with a hint of regret, having disposed of an adversity that ultimately gave her more depth of personality? Do the family photo albums of the brown 1970’s lose something when they are retouched into thousands of vivid colors? Have you ever watched a colorized movie that was better than the original?

People with color blindness see forms, shapes, and textures in different ways than people with normal vision. They are less tricked by camouflage, making them valuable members of a hunting party, which possibly explains the relatively high prevalence of this “deficiency.” Human tribes with a few of these hunters might have better spotted the silhouettes of additional prey hiding in a shifting, textured forest. Color blind men were also used for this reason in World War II to see past the German military camouflage designed by and for those with normal color vision. Are there more subtle benefits for humanity to have some see this world in a dissimilar spectrum? Paul Newman, Bill Clinton, Jack Nicklaus, and Mark Twain were all color blind.

But should gene therapy work someday, and men with color blindness are cured, one thing is for certain. They will be fully responsible for wearing green socks with tan corduroys and a purple sweater to work. What is uncertain, however, is how many would want to change their imperfect perception of the world.

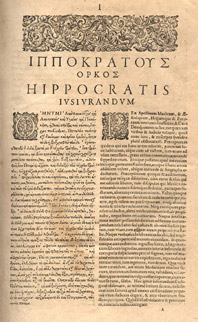

I’d like to wish all the medical students beginning their arduous four-year med school journey this month the best of luck. Reminiscing on my first days of medical school, I recall the thrill of reciting the Hippocratic Oath for the first time as part of a ritualistic White Coat Ceremony. It felt like the incantation somehow connected me to a long line of great men, from Hippocrates to Benjamin Rush to my childhood family doctor. It marked a distinct line between the life I had already lived and the medical profession that was to become a considerable part of my identity. But is the Hippocratic Oath an outdated, out of touch relic in the complex modern world?

I’d like to wish all the medical students beginning their arduous four-year med school journey this month the best of luck. Reminiscing on my first days of medical school, I recall the thrill of reciting the Hippocratic Oath for the first time as part of a ritualistic White Coat Ceremony. It felt like the incantation somehow connected me to a long line of great men, from Hippocrates to Benjamin Rush to my childhood family doctor. It marked a distinct line between the life I had already lived and the medical profession that was to become a considerable part of my identity. But is the Hippocratic Oath an outdated, out of touch relic in the complex modern world?

The original oath swears to deities that no longer “exist”, makes unreasonable promises of servitude to teachers, mandates free tuition, possibly forbids abortion and seems to prohibit surgery. Yet almost 100% of medical schools in the Unites States administer some contemporary adaptation of the Hippocratic Oath. According to the AMA’s Code of Ethics, the Oath of Hippocrates “has remained in Western civilization as an expression of ideal conduct for the physician.”

Has it? In all fairness, no one really recites verbatim the actual translation of Hippocrates’ Oath any more. Most medical schools use variations that preserve the best qualities of the oath, such as compassion and “first doing no harm,” and omit the tenets that seem bizarre in a modern context.

But let’s consider, line by line, the original Oath and how well it holds up, both literally and figuratively, for today’s medical physician, and then let’s see if we can distill it down to a 140 character tweet.

The Hippocratic Oath

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses*, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant:

* While Ancient Greek Polytheism is certainly available as a choice of religions, it is not required that all medical students have a personal connection and faith in Apollo, Asclepius, et al, for the terms of this Oath to be meaningful. But the very act of swearing to a higher power, whether it be to a god or personal sense of honor, is a fundamental human tie that binds marriages and professions with a sense of duty and principle.